The Women of Penn

What distinguishes Penn Relays from other noteworthy track and field meets? Ask the event’s current director, Dave Johnson, and he’s quick to rattle off a list of superlatives: it was the first track meet dedicated to relays; it is the largest annually-held track meet in the world; it is the meet with the longest uninterrupted streak of competition. The legendary Philadelphia “relay carnival” was born in 1895, and today is considered one of the biggest track meets in the United States, drawing crowds of over 100,000 to Franklin Field each year, over the course of three days. The meet caters to male and female competitors across high school, college, and master’s levels, in addition to some races for kids — 2015 saw more than 22,000 entries, and Johnson tells me that the competitors’ age range has spanned from as young as seven to as old as 101. With such a lengthy andinclusive history, you might be surprised to discover that women’s events have only been a part of the story for the last 50 years.

Women’s competition at Penn Relays began in 1962 — the 68th iteration of the meet — when the only women’s event was an invitational 100-yard dash. Nine women were invited to race, and the extraordinary Willye White took home the win, clocking 10.9 seconds. White, who died in 2007, went on to become the first five-time Olympian in the history of American track & field, competing in every Olympics from 1956 to 1972. Over the course of her career, according to the New York Times, she earned a place in eleven different halls of fame. White’s presence and victory at the first Penn Relays for women sent a clear message: from their very inception, women’s events at the meet would attract competition of the very highest level.

Beyond Penn Relays, the climate for women’s track and field at this time was gradually evolving. Scholastic and collegiate women’s track programs were all but nonexistent; women who sought to train and compete were often limited to club teams, which were few and far between. Two years before the Relays’ inaugural women’s dash, at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, American track star Wilma Rudolph had taken home three gold medals, winning the 100-meter dash, the 200-meter dash, and anchoring the winning 4x100 meter relay. As Louise Mead Tricard writes in her book, American Women’s Track and Field: A History: “Wilma represented thousands of dedicated women in the United States who for 65 previous years faithfully trained and victoriously competed in track and field with little encouragement, support, opportunity, or recognition.” (Incidentally, Mead Tricard was also part of the field in that first 100-yard dash at the Penn Relays. She placed fifth.)

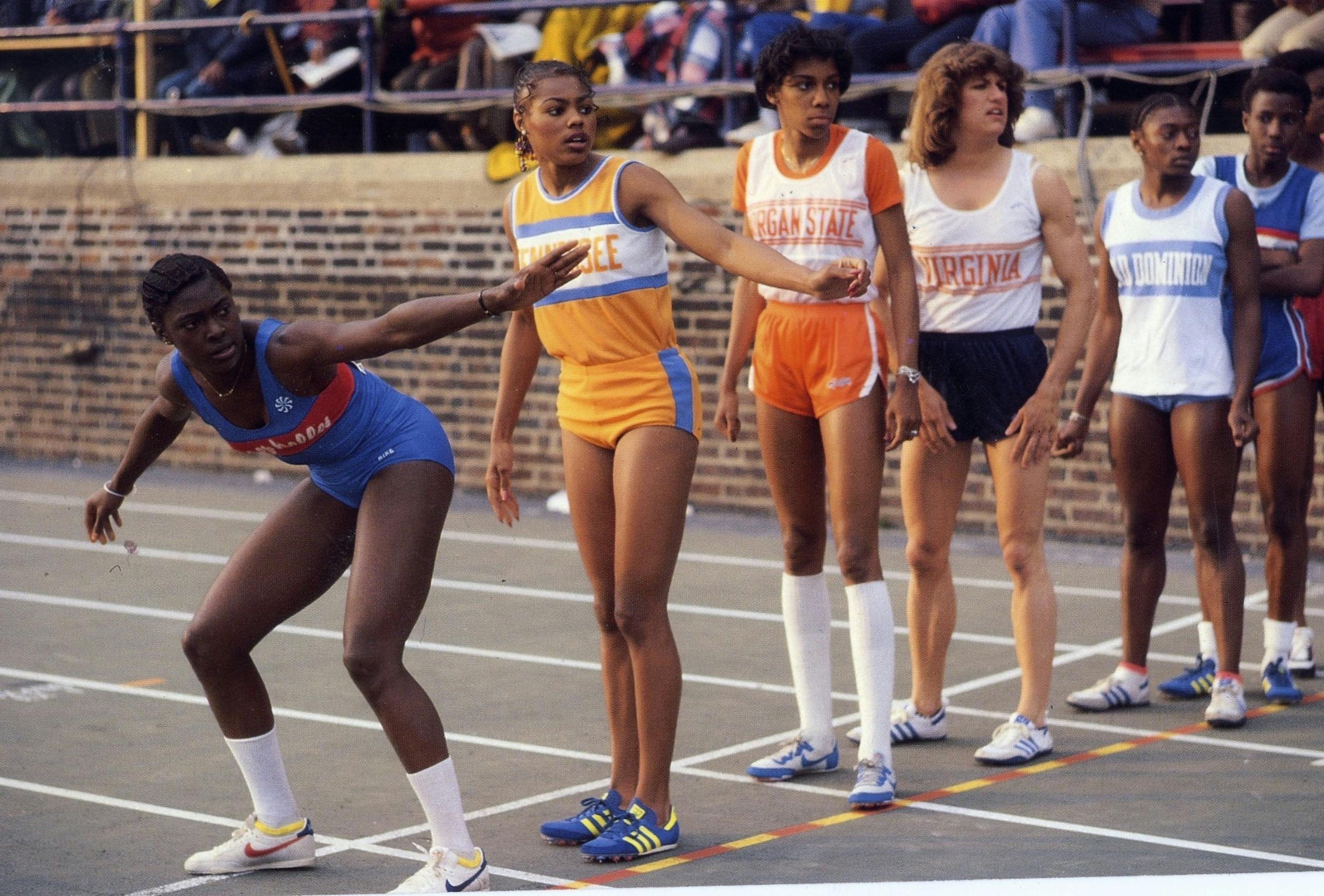

Delisa Walton-Floyd (Tenn)

Johnson tells me that even though Rudolph didn’t race at Penn Relays, the initial decision to include women’s events was “very much due to” her accomplishments in Rome in 1960. “In 1961, several indoor meets on the North American track circuit put in a women’s dash, [in an attempt] to get Wilma Rudolph there,” he says. The following year, Penn Relays jumped on the bandwagon. That initial dash in 1962 acted as the gateway to the expansion of women’s competition at the Relays: In 1963, the first women’s Olympic development relay was added to the program, and 1964 brought the addition of a high school girls’ 440-yard relay. As Mead Tricard writes in her book: “Wilma’s triumphs, with the whole world watching, symbolically and in reality were the phenomenon that broke the shackles that bound women’s track and field and forced America to recognize and accept women in this sport.”

In 1962, the Olympic Committee and the physical educator’s association joined forces in an effort to revitalize the development of women’s track and field programs. The number of women’s events at Penn Relays gradually increased during the 1960s and 70s, as women’s track continued to expand in schools nationwide. In 1972, Title IX legislation took effect, and collegiate women’s sports began to expand. Around the same time, high schools around the country began adopting girls’ track at the state championship level. By 1978, Penn Relays added a third day of competition, with one day devoted entirely to women’s events. “When [then-meet director] Jim Tuppeny started the women’s day in 1978, there was a fear that there might not be enough interest on the women’s side,” Johnson says. “He was very wrong on that, and it expanded very quickly.” Penn Relays rapidly became one of the most significant track and field meets for high school and college women, both on the East Coast and well beyond.

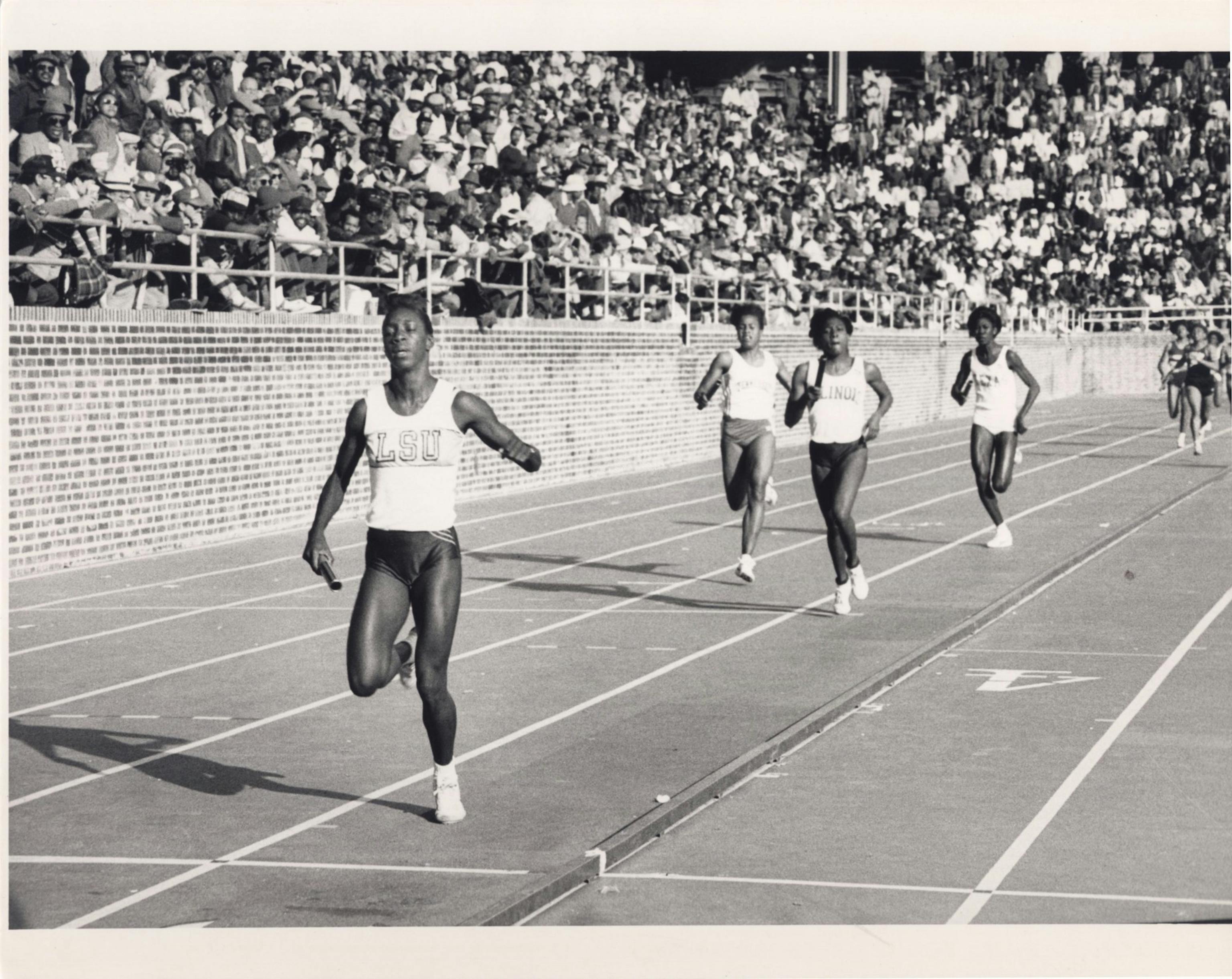

Schowonda-Williams

In conversation, Johnson highlights a handful of club team coaches who he considers key players in the fight for women’s track and field during the 1960s and 70s. Among this group of coaches was Bill Thomson, who coached the Delaware Track and Field Club from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, and worked for many years as a race official at the Relays. Thomson first attended the meet as a child in 1938, when his mother took him to spectate the races. “It’s the biggest, oldest, and the best track meet in the world,” he tells me matter-of-factly, when I ask about what makes the Relays so special. During his years as an official, he initially served as the “women’s referee”, but he eventually convinced Tuppeny that women’s competition was a significant enough part of the meet that he should simply be a collegiate referee, and that the female athletes didn’t need a separate official. The lineup of women’s events continued to expand, and Tuppeny granted Thomson’s request.

In Thomson’s family, the Penn Relays became a family affair. His daughter, Carol Slowik, has participated in the Relays as an athlete, coach, official, and spectator over the years. She tells me that her father is considered “one of the pioneers for fairness in the sport”, and credits him for exposing her to the meet growing up. She raced there in the late 1960s as a high schooler, and the meet had a profound effect on her as a teenagerunner. “It’s a wonderful thing for young girls to see the women at Penn Relays and how fiercely they compete,” she tells me, adding that the atmosphere of the meet “really told women that they could be on same playing field as men.”

Slowik went on to have an exceptionally successful running career as a hurdler, winning a national collegiate title in the 100-meter hurdles while at University of Delaware, and garnering two American records and a world record in the shorter hurdle races. By the 1980s, she had become the head women’s track and field coach at the University of Florida. The women’s races at Penn Relays had expanded — on both the high school and the collegiate level — and there was no question that she wanted to bring her own athletes there to experience the thrill of a top-notch competitive atmosphere. She tells me that Penn Relays “has done a tremendous amount to open up a lot of avenues for women” across the sport. In the late 1980s, Slowik became a race official at the Relays, making her the meet’s first female starter.

Slowik’s trajectory — returning to the meet for decades in a series of different roles — was not that unusual at Penn Relays. Many of the coaches I spoke with had competed at the meet during their own athletic careers, and found the experience so exciting, and the competition so exceptional, that they prioritized adding Penn Relays to their meet schedules.

Another example of this phenomenon is Gina Procaccio. A recent addition to the Penn Relays Wall of Fame, she started out running at the Relays as a high schooler in the late 1970s and early 80s. “They call the meet a carnival — and it lives up to its name,” she says. As a high school runner, she tells me, “You start out as one of the many thousands and thousands … and maybe you have dreams of winning the Penn Relays one day.” But Procaccio isn’t speaking hypothetically — she has a great deal of experience finishing first at the meet. In her senior year at Villanova in 1987, she ran on the winning distance medley relay. Then in her post-collegiate running career, she went on to become the Relays’ most successful runner (female or male) in the mile or 1500 meters, taking first place fives times in that event, in addition to winning the 5000 meters once in 2000.

Procaccio is now the head coach for the women’s track and field team at Villanova, and her athletes have dominated Penn Relays in recent years. Among a lengthy list of accolades, they have won the distance medley relay four years in a row, and have taken home three consecutive “Championship of America” titles in the 4x800-meter relay — an event for which they hold the all-time collegiate record. While Procaccio has grown very accustomed to successful races at the Relays, she says the meet has grown consistently more competitive over the years. She also believes that the Penn Relays schedule shows a unique commitment to women’s track and field, saying: “There are not too many meets who will dedicate a whole day to high school girls and college women.”

Alisa Harvey (L)

Penn Relays’ influence extends beyond American borders, too. Branwen Smith-King — the assistant athletic director at Tufts University and a self-described “track nut” — grew up in Bermuda, but says that Penn Relays’ reputation had no difficulty reaching her. “Penn Relays was always the mecca of the sport,” she tells me. “People all over the world knew about it.”

Smith-King competed as a thrower at Springfield College in the 1970s. She recalls training for a few years without a coach before the team evolved from club to the varsity level, but when a coach finally came along in her junior year, he insisted on bringing her and some of the other athletes to Penn Relays. Smith-King competed in the shot put, and she won. She later went on to become an All-American in the shot put, setting multiple (still-standing) school records along the way, and eventually became the women’s track and field coach at Tufts. During her Tufts coaching tenure in the 1980s and early 90s, she would bring her most promising relay teams to compete at Penn Relays. At that time, due to an old conference rule, she could only bring individual athletes to nationals, but not relay teams. As a result, competing at the Relays became a reward for her top athletes’ hard work. “Penn Relays was like our nationals,” she explains. To Smith-King, the significance of the meet cannot be overemphasized. “If you’re anybody in the sport, you’ve probably done Penn Relays,” she says.

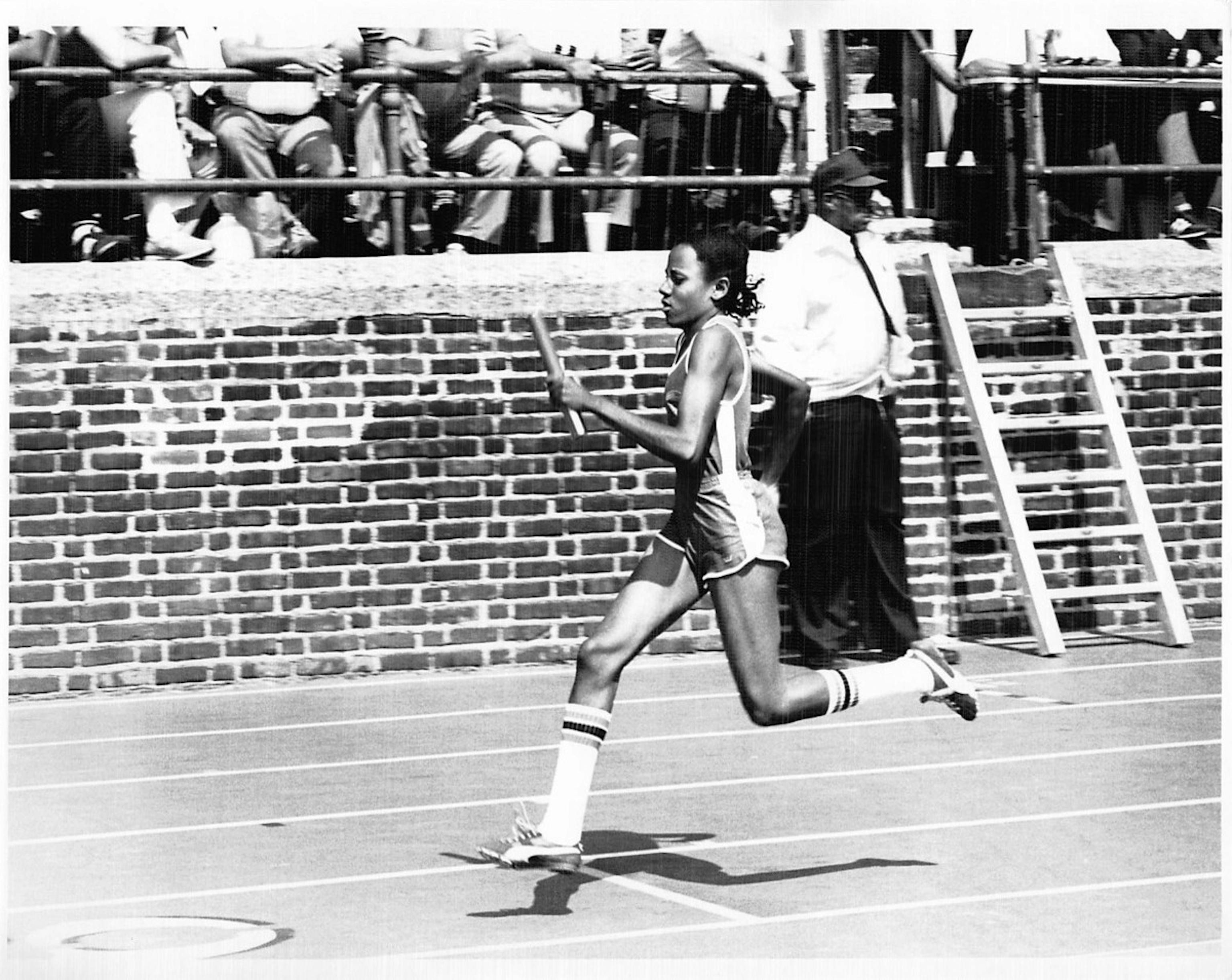

Randy Givens

For many, the existence of the women’s day at such a prestigious meet in an enormous venue sends a powerful message about how much the recognition of women’s track and field has progressed. Vin Lananna — the president of TrackTown USA, associate athletic director at University of Oregon, and the head men’s track and field coach for the 2016 U.S. Olympic team — has been bringing athletes to the Penn Relays since 1975, throughout his career as a coach at Dartmouth, Stanford, and the University of Oregon. He says that the day dedicated to women’s events is only fitting: “In the sport of track and field, really unlike any other sport, I think there is a tremendous similarity between the men’s [competition] and the women’s.” The University of Oregon has hosted the NCAA Division I track and field championships multiple times during Lananna’s tenure at the school. For that meet, he tells me, they also made the decision to split the men’s and women’s events into different days of competition. He recalls similar skepticism about whether the women’s day would be well-attended. “But the women outdrew the men,” he says. “In the sport of track and field, women’s track is a standalone.”

At Penn Relays today, the range of events for women and girls has grown immensely from that single 100-yard dash in 1962. Some of the most talented high school and college athletes in the country travel great distances to toe the line in Philadelphia, and the “USA vs. the World” relays attract a handful of international standouts. Smith-King describes Penn Relays as “a positive environment for women to excel,” recalling that the level of competition over the years was comparable for the women and the men. She believes that the meet has “a huge contribution” to both the development and the recognition of women’s track and field. A cursory glance at today’s extensive women’s results at Penn Relays can make it easy to forget how recently the disparity between men’s and women’s events persisted. As Smith-King puts it: “Women’s sports in this country have come a long way, in terms of opportunity and equity. We need to keep that history alive.”

Ethlyn Tate

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Molly Mirhashem is deputy digital editor at Outside Magazine. This story originally featured in issue #03 of Meter magazine.