KENYAN LESSONS

Words by Adharanand Finn

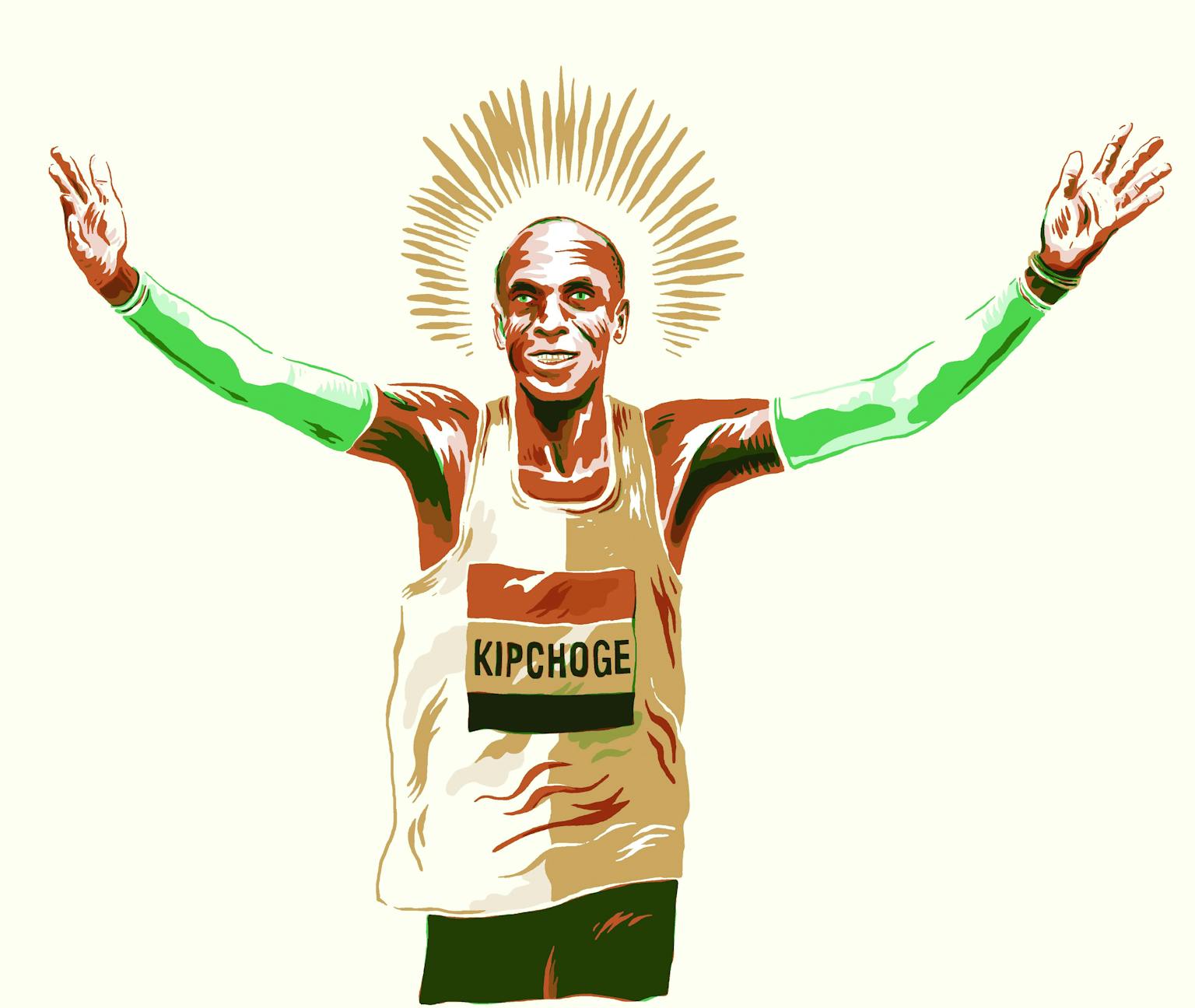

Illustrations by Jindřich Janíček

East Africa hasn’t come to dominate global distance running by chance - science is putting theory to the culture that has created that success. What can you learn from the Kenyans? Author Adharanand Finn found out the hard way, on the dirt roads of Iten.

It’s just before 6am and I’m standing at the junction of two dirt roads in the small town of Iten in Kenya’s Rift Valley. As I wait, figures emerge out of the darkness and without much talking, just the odd handshake, a large group of around 50 people starts to form. At 6am on the dot the group huddles closer together, before, on some imperceptible signal, we all begin running.

Before I first went to Kenya, I had no idea how I was going to keep up. This is a town where a 2:08 marathon is nothing to shout about. With my half marathon PR of 1:26 I was way out of my depth.

But 10 minutes in, as the sun begins to rise, I’m chugging along easily in the middle of the group. Nobody talks as we wind our way through the lush, fertile land, past mud huts and children wrapped up in shawls trotting to school. The only sound is the soft murmur of hundreds of feet landing lightly on the earth.

I end up getting dropped near the end of the 12-mile run, but in this one scene, repeated over and over most days in Iten and Kenya’s other running centers, are so many lessons that any studious amateur runner may want to think about and learn from. After all, who better to emulate than the Kenyans?

Pole pole, slowly slowly

Firstly, to my surprise and relief, Kenyans do a lot of their running slowly, or “easy” as they call it. And I mean really slowly. If you’ve been labelling your 7 minute/mile pace runs on Strava as “recovery”, you may be interested to know that these guys - and I ran with world record holders and Olympic champions - are often running 9 minute/mile pace or slower. The first time I joined them on an easy run, I thought they were having a joke at my expense it was so slow. But no one was laughing.

There’s a whole science behind the benefits of slow, easy running, but I doubt even Eliud Kipchoge could tell you exactly what it is. They just know that it feels right, and that it works. “You need to let the body recover,” they’ll say. Or, “we go easy today, so we can go hard tomorrow”.

Of course, it’s not all easy running, and you don’t want to turn up on a hard day by mistake, as I once did. Not unless you’re Galen Rupp or someone. The amazing thing about Kenya is you can just show up to a random group, and even as a slow-coach like me they’ll let you join in without question. Except that fast day, when there were a few concerned faces. The group leader that morning, a certain Wilson Kipsang, came over to me. “You know,” he said, “today is fast.” OK, I thought, I’ll just run for as long as I can, even if it’s only half a mile. In the event I lasted - sprinting - less than 200 metres.

The value of slow running was one of my biggest takeaways from six months living in Iten. One coach, Ian Kiprono, told me the reason for running slowly is partly so that the body - and hence the mind - doesn’t start to dread training. “If you always push,” he said, “the body will start to fear training. But if training is often easy, and then sometimes you push [hard], the body will be more accepting.”

Feel the way

This gentle coaxing of the body, listening to it, is key to the Kenyan approach. Almost every runner has a watch, but they rarely look at it during the run, or record or analyse the information in any way. Owning a watch is a sign of success, so they wear it and start it as a badge of status. But they’re never judging their pace by it. Instead, everything is done on feel. Easy. Hard. Medium. Maintain. Push.

And if the body doesn’t feel good, they’ll stop. If they have a training program - which very few do - completing the schedule is not important. In a land with few physios, injuries are feared more than anything.

“We have to go up to that line,” coach Brother Colm O’Connell tells me, “but never cross it.” He means the line where pushing too hard, or through pain, leads to injury. And the best way not to cross it? To listen to the body, not the watch.

This sounds simple, but of course, simplicity is often one of the hardest things to achieve. Are we really hurting, or just not in the mood? And it’s especially hard if you’ve outsourced your internal monitors to your watch.

Morning people

Another thing that fits with the latest science, but which the Kenyans do simply because it’s what they’ve always done, and because it works, is to do their easy runs before breakfast. If you ask them why, they won’t mention fat adaption, but by running easy on an empty stomach your body learns to burn fat more efficiently.

For harder workouts, which are better fuelled with carbohydrates, the Kenyans will usually eat first and then run later in the morning. A typical breakfast is millet porridge, and tea with lots of milk and sugar.

Milky, sugary tea is also the Kenyans’ favorite recovery drink after a long run. I once joined a top group - including an Olympic marathon champion - on a 25-mile run before breakfast. Along the way they were only drinking water, and by the end they were running close to 5 minute/mile pace. Yet afterwards, all they had to recover was Kenyan tea.

The diet of the Kenyan runners is generally rich in carbohydrates, mainly out of necessity, as grains and vegetables are the cheapest and most easily available food source. At one training camp I stayed, they had a menu on the kitchen wall, which was amusing as it was the same food every single day: rice and beans for lunch (this will often include carrots and potatoes), and ugali and stewed kale for dinner. Ugali is the famous Kenyan staple food - made from maize flour and water, it’s bland and simple, but the athletes swear by it.

Harambee

Of course, we all know how good we feel after an early run, but most of us struggle to get out the door in the morning. In my experience, the sparsity of pillows and fluffy duvets on the beds of most Kenyan athletes helps - even the most successful runners often live in simple, stripped down training camps.

It is also easier to get up to run if you have people waiting for you. The power of the group is key in Kenya - even the Kenyan national motto is harambe, which means “all pull together”. Not everyone likes running in a group - and indeed not all Kenyans do - but it has many advantages and most Kenyan runners are part of a training group of some kind. Being part of a group pushes and motivates the runners to do work hard and do their best, and the bar is set pretty high when some of the members of your group are Olympic medalists, world record holders, or at the least athletes who have raced professionally and brought home large sums of prize money to transform their lives.

The spirit of togetherness engendered by these training groups is powerful and you’ll often see Kenyan runners celebrating another Kenyan’s victory like their own. Without a system of funding for up-and-coming athletes, the more successful runners will often support their training partners, giving them shoes and running gear, helping transport them to training and even with food.

Sound of silence

One thing it’s impossible not to notice when you run with Kenyans is their beautiful form. They all seem to glide along effortlessly, and even when they’re pushing the pace, it’s rare to hear them breathing hard. This form is difficult to mimic as it comes to them naturally from a childhood spent being active and running around everywhere barefoot. But it illustrates the importance of form in running fast - they are getting so much free momentum from their elasticity and from gravity. Changing the way you run is not without its potential problems, but if you can find a good movement coach it’s certainly something to consider if you really want to run like a Kenyan.

The last lesson I learned during my six months in Kenya is in some ways the easiest to implement, but also the most difficult. Kenyan athletes love to sleep. They go to bed early, and spend much of the day, when they are not running, simply asleep, or sitting around doing nothing. We may think we’re resting looking on our phones, sending emails or reading the news, but we’re still switched on mentally. In the training camps I stayed, by 9 o’clock I would find myself sitting up alone. Everyone else was in bed. Yet at home in England, no matter how hard I try, I never seem to be able to convince myself of the merits of an early night until it’s too late.

This is beginning to change in Kenya, too, however, where smart phones are becoming more and more prevalent, reaching parts of the country McDonald’s never did, including Iten. Who knows, perhaps, in the end, it will be Facebook that brings the downfall of Kenyan running.

This article originally featured in the Fall 2019 issue of Meter Magazine, Tracksmith's quarterly journal of running culture. Adharanand Finn is the author of three books on running and the host of the Way of the Runner podcast.